When I give

presentations, I am often asked the difference between pirates and privateers. In

fact, pirates and privateers, though not legally alike at all, were very

closely linked in actual practice.

First – the definition.

Pirates – people who commit

robberies at sea.

Privateers – ships or

ship’s companies with a license – called a letter of marque – issued by their

government to attack enemy shipping during wartime.

Not much in common,

right?

If you’ve been reading

this blog, you know a lot about pirates, but let’s look a little more closely

at the practice of privateering.

Why did privateering

start? The need to license privately owned ships into Navy vessels may be caused

by many things. Ships might be needed quickly – such as due to a sudden

outbreak of war. It can take years to build a warship, so acquiring the

services of existing vessels is a quick way to get warships.

Another pressure that drove

the need for privateers was a lack of funds. If a country was under-funded, it

would be cheaper to license privateers than to fund navy ships. Privateers paid

for the right to carry a Letter of Marque, and they brought income into their

nation’s treasure through captured goods.

At the time when

privateering was common, it was lawful for nations to capture civilian merchant

ships during war. Normally, a percentage of the value of the captured ship and

cargo was divided among the officers and crew of the capturer, and the rest

went to the nation. The owner of the captured ship was simply out of luck

unless he had insurance.

Once a ship had been captured,

it became a “prize.” The capturing ship put a small crew aboard the prize,

which sailed it to one of many designated “prize ports” where the ship would be

examined by specialists hired by the navy.

|

| In this cartoon, the officer asks if the sailor is frightened. The sailor replies that he prays that the casualties will be distributed the same as the rewards (meaning that almost all will go to the officers.) |

The value of the ship and

cargo was determined, and the ship and goods would be auctioned off, or else

purchased by the navy (if, for instance, the ship could be used as a war ship,

or the cargo was some sort of material valuable to the military.) Funds made

their way back to the capturing ship in a few months. Oftentimes, however,

banks would issue loans to the sailors, holding their share of the captured

ship as collateral.

Many, many ships began as

war ships for one nation, and ended up serving another after being captured.

And many, many navy captains made fortunes by capturing valuable goods from

their enemies.

Privateering ships did

much the same job. They were intended to disrupt enemy shipping. But if they succeeded in capturing prizes, the money was

split between the ship’s owner and its captain and crew. The owner of a

successful privateering ship might become immensely wealthy.

Of course, he might also

lose his own vessel, sunk of captured, during the first battle. It was simply a

gamble, one in which only the licensing nation was sure to win. Only the license

and the fee were a sure thing.

So what has this got to

do with pirates? For one thing, if a privateering ship did not have its

paperwork in order, it could be condemned as a pirate, even by its own country.

The ship was forfeit, its captain and crew jailed for piracy. The owner could

counter-sue, and sometimes these cases were in court for years.

But this depended on

getting caught, or even who caught you. There was the issue of probable cause. Navy

ships were supposed to keep privateers in line. But why bother to inspect the

paperwork of a ship fighting on the same side as yourself?

It was more likely to

happen to someone who annoyed navy captains or the officials of a port. If

paperwork was not correct, a privateer captain might lose everything. Or his

transgression might be overlooked because of friendship between captain, a

dislike of bureaucracy, or simple bribery. Like privateering itself, this was a

gamble.

Captain Morgan - of rum

fame - often raided Spanish towns when he did not have authority to do so. But

the huge amounts of money he shared with government authorities kept him out of

trouble. And during the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin wrote and sold many

Letters of Marque to patriots and opportunists. His motivation was to increase

the power of his nation, but he did not have the right to issue these

documents. Everyone carrying a Letter of Marque signed by Franklin was,

technically, a pirate.

Privateers also

deliberately became pirates. The captain and crew of a privateering ship were

not paid a salary. Instead they worked on a “No prey, no pay” policy. So if a

privateering ship had not captured any enemy vessels for while it might start

to “fudge” the rules, attacking ships that were neutral or even allies.

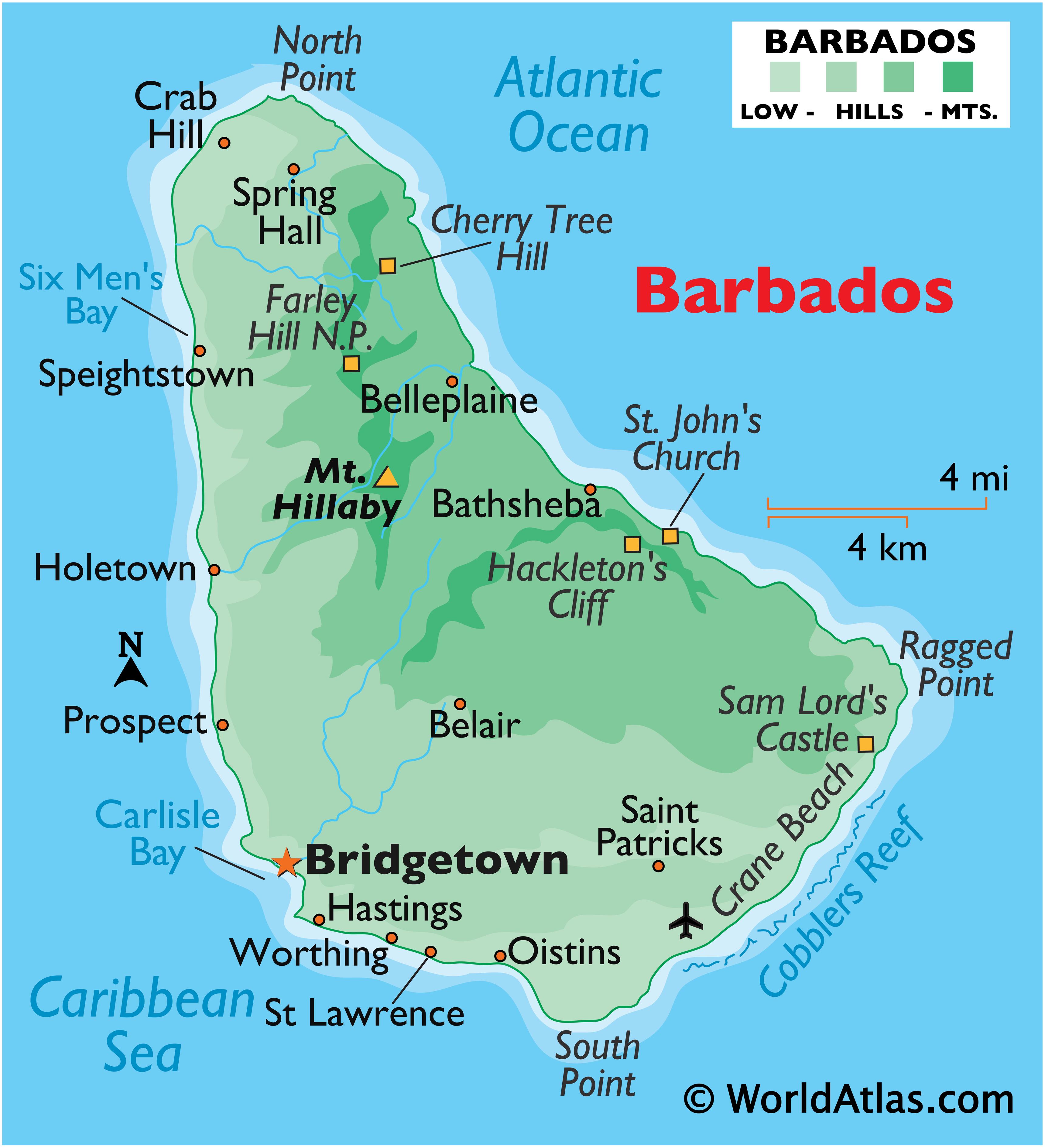

In this case, the privateer’s

men were counting on not being caught. This happed more frequently when a ship

was far from home – The Indian Ocean and the Caribbean were both prime

territory for a ship to practice a little piracy, with the hopes than no one

back home in Europe would find out.

After a privateer had

made one illegal attack, it might give up on lawful practice and simply go turn

to piracy. Or, once might be enough, and the ship would follow the

straight-and-narrow ever afterwards.

Sometimes these wayward

privateersmen were discovered years later, and lawsuits would be issued. At

this time, the captain of the privateering ship would claim that he believed

that he had a legal right do whatever he was in trouble for. The ship’s former

owner would demand satisfaction. Court cases, once again, dragged on for years.

And, just as privateers became

pirates, pirates sought to cover their activities be claiming to be lawful

privateers. Some may have even thought of themselves as acting legally. Ben

Hornigold refused to attack English ships for just this reason. Captain Morgan never

considered himself a pirate. Men like Francis Drake and John Hawkins were

considered heroes by their own nation, and pirates by the Spanish whom they

robbed.

Lastly, pirates did not

want to advertise that they were pirates while in port. While on land, they

wanted to have a good time, not clash with the authorities. So the word “privateer”

would be used, often with a wink, a nod, and a maybe gold coin to whoever was

asking. And if the man in question was buying drinks, who cared?

|

| Every sailor's dream returning home safe to a loving family - And with enough money to impress the mother-in-law! |

:origin()/pre13/9c08/th/pre/i/2004/09/5/2/me_scorvy_dog.png)