If you want to create a notable pirate character, there is some good news and some bad news. The good news is that many other writers have done, or tried to do, the same thing and you can learn from their triumphs and mistakes. The bad news is that your character will be competing with some of the most famous and iconic characters of all time.

Let us start with the earliest example of a famous pirate – Long John Silver from Treasure Island. He’s one of the most well-known of pirates, and also the guy who began the image of the pirate with a peg-leg (thought Silver never actually had a peg, using a crutch to walk instead).

Silver is famous for both his ruthlessness and his humor. He is a man dedicated to one goal – the retrieval of Captain Flint’s buried treasure. He will do anything to get it…. He starts off by selling his prosperous business. He lies, cheats, bullies men stronger than himself, stands down a mutiny, all in the name of the buried gold.

But at the same time, Silver is everybody’s friend, at least on the surface. As the ship’s cook, he has opportunity to pass out treats and extra food rations to both his compatriot pirates and his young protégé, Jim Hawkins. He is subservient to Lord Trelawney and the ship’s officers, even as he is plotting to kill them. And he comes to genuinely love Jim.

So, like a real person, Silver is a mass of contradictions. Kind but ruthless, intelligent, but with limited goals, a leader with no official title, a terrifying bad-guy who is also a cripple. (It should be noted that Silver was based on a real person, a man of great character, who had lost a leg to disease.) These should be the rules for creating any fictional character- or at least one that you intend to be a star. Build in contradictions. Somehow, if he had not been missing a leg, Silver would not have been so frightening.

And yet, I believe that even these contradictions are not the final touch that seals Sliver as such a great pirate. What makes him stand out is his softness for Jim Hawkins. He gives up everything, simply because Jim is a young man who has looked up to Silver, and Silver sees the good in the boy. That’s the moment – when the one-legged pirate pulls his pistols and stands up to his own men, for the sake of a boy who cannot help him at all, that Silver wins out heats.

To put it simply, Silver’s greatest strength – his ruthlessness – is overcome by his greatest weakness – his love for Jim.

Remember that – a really good pirate is neither all good not all bad.

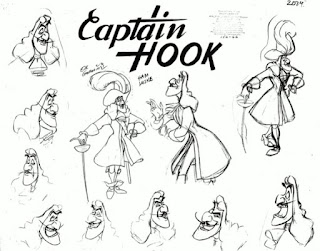

But what about Captain Hook? This is a bad guy. His nemesis is an innocent child. He kidnaps an Indian princess, threatens to murder the Darling children, captures and nearly kills Tinkerbell. (Murdering fairies, for heaven’s sake!). Where is the redeeming feature that makes Captain Hook more than a cartoon bad-guy?

Because, like so many people in the audience, Hook can never have what her really wants. Hook wants to be a proper English gentleman. He shows us this by his insistence on “good form”, by his careful diction, his immaculate clothing. Hook went to Eaton, and sets a great importance on this (his dying works are Eaton’s motto).

Hook is, in some ways, the ultimate Adult to peter’s ultimate Child. Like adults (especially adults as seen by children) Hook is all hung up on appearances. He needs to dress right, use the right manners, to always be in control. Unlike the “Indians” who admit they are playing a long-running game with Peter and the Lost Boys, Hook is serious.

But Hook’s problem is that his is, at heart, a coward. And he hates himself for it. He’s not only defeated by a child – Peter – but he is humiliated by him. Hook admits to being a “codfish” and weeps with terror when his own life is on the line. This turns his elegance and self-possession on its head.

Hook has a lot in common with Daffy Duck. They both care much-too-much about winning, and as a result, they fail. Daffy’s comic failures make us love him; Hook’s failures take some of the bite out of his truly frightening and horrible behavior.

Hook also has Smee, another of our famous pirates. Smee is the opposite of Hook. Where Hook is formal and passionate, Smee is easy-going; when Hook is well-dressed, Smee is comfortable. They complement each other. Smee is a good reminder to all writers that no pirate stands alone, and that a single well-drawn side-kick can stand in for a whole crew. Imagine for a moment if Smee was a heartless killer like Hook? The pirates would lose all their humor and be too frightening, rather than frightening and fun.

And speaking of “fun pirates”, what can we learn from Captain Jack Sparrow? It’s interesting to note that all of the pirates on this list have a simple theme behind them. Long John Silver is a ruthless killer with a heart of gold. Hook is a fearsome pirate with perfect manners, who conceals his own cowardice. And Smee is the perfect sidekick, the guy who keeps Hook form being too scary. Captain Sparrow also has a simple concept – he is a pirate who lives like a rock-star.

How does Captain Sparrow accomplish this? Well, for one thing, he reads his own reviews and writes his own press releases. Jack takes his reputation very seriously. His pronouncements –You will remember this as the day that you almost caught Captain Jack Sparrow…- are funny, but they also tell us a lot about what Jack cares about. And what he cares about his being famous. This is a relatable goal, especially for modern audiences. We’d like to be famous, too.

The fact that Jack doesn’t quite succeed in his plans for fame – even as he’s being hanged, the authorities refuse to acknowledge his as “Captain” – makes us care for him more. He’s got our sympathy.

But Johnny Depp did one more thing that cemented Jack as a pirate of historic significance… When confronting Will Turner in the blacksmith shop, Johnny was supposed to tell Will “This shot is not for you” and then cock the pistol. Jack Sparrow cocked the pistol first, then said the line. This is important, because it sent a message that Jack was serious. He didn’t WANT to kill Will, but he would, if necessary. The threat was real. And the threat of actually killing Will keeps all of Sparrow’s other problems… His wandering walk, his issues with the authorities, his loss of the rum… He will kill people, even an innocent like Will. Without the threat, he’s no fun.

What have we learned? A memorable pirate character needs to have a good mix of threat and sympathy. It should be well-rounded, having the kind of internal contradictions that real people have. The pirate should not exist alone… One pirate needs other pirates to be an effective character, and the contrasts between pirates offer depth and interest. And last of all, it’s a wonderful touch to have the pirate’s greatest strength also be his or her greatest liability.

I have high hopes for my own character, Scarlet MacGrath. As a female pirate captain, she stands out from the crowd. But she also faces problems caused by her gender. She a realistic woman in that she can’t go toe-to-toe with a man in a fist fight. The men around her are too strong. But she makes her weakness into strength by out-thinking her opponents.

Scarlet means business… She will kill if she has to. But she doesn’t want to. In fact, my fearsome, treasure-loving, pistol-shooting, sword-carrying Irishwoman secretly longs for a home, a husband, and a couple of kids.

See how that’s working out for her in my pirate novels, Gentlemen and Fortune, in which Scarlet meets old enemies and new lovers, and handles treasures of many kinds. And in Bloody Seas, where she confronts bloodthirsty natives, old enemies, and a Royal Navy Captain that she doesn’t know if she’d like to kill or kiss…

http://www.amazon.com/TS-Rhodes/e/B00FD66IL6

Fascinating facts about Pirates, their lives, weapons, ships, and history, by the author of The Pirate Empire, available on Amazon.

Monday, July 27, 2015

Monday, July 20, 2015

The First Pirate

A question that comes up on a regular basis is “Who was the

first pirate?” When you are looking at just the Golden Age of Piracy, I’d have to

give that title to Francis Drake (c 1540 to 1596) But when you look at the

larger issue – at all the pirates that have ever lived, the question (like so

many things about pirates) gets a lot murkier.

Piracy began with boats, and boats go back a long way. So

long ago, in fact, that things like “laws” are hard to pin down. The earliest

forms of piracy – practiced by the ancient Greeks and Phoenicians – was simply

a matter of attacking people weaker than yourself, beating them up and taking

their stuff. At the time, this was pretty much how all “international law”

worked.

Piracy was something that was done to you. If you did it to

somebody else, it was skirmishing, raiding, or “viking” depending on where you

were, and it was perfectly all right. Nations just did this to each other. The

Irish and the Scots were great raiders. All the Celtic tribes practiced

raiding, and the Greek city-states had very small wars going on almost

constantly over just this kind of thing.

The main reason the Norse were so hated for their “viking” was

that they were just so good at it. Plus, the people they attacked didn’t have

boats equal to the Norse longboats. This meant that the victims couldn’t go raid back, as was the custom.

A little closer to home for my American readers is the

practice of the Native Americans. Young men of many tribes raided the

neighbors. Horse-stealing was a fine art. It proved the initiative of the

raider, enriched him, and made him look sexy for the girls. And while it wasn’t

fun for the victims, this sort of thing wasn’t “war” in the sense that we

understand it. It wasn’t about destroying people or goods. It was about getting

rich.

If the raiding got out of hand – if too many innocents were

hurt, if too much damage was done, older people would be called in to negotiate

reparations. The Celtic tribes used similar methods to keep something like

peace. It was mostly a matter of young men playing. And, as they say, whenever

men play, they play at killing each other.

Which leads us to pirates.

The early Golden Age pirates – called the Buccaneering

pirates – Raleigh, Drake, Hawkins, Morgan, were raiders in the old sense. Spain had money. England needed money. And

Spain’s money was on the other side of the world, where no one was looking at

it too closely. So these men showed

their initiative by taking that money, bringing it home and sharing it with their

own government.

The biggest differences here were the growing nationalism in

Europe, and the issues of religion. The English

raiders were Protestants, and to the Catholic Spanish, they were just as much

Godless heathens as Muslims or American natives. The Spanish believed that God

had given them all of North and South America, with the attendant gold and

silver. Anyone stealing this money was acting against the wishes of God.

For this reason, the Spanish executed English pirates as

soon as they caught them. This was hardly new- people had been killing pirates

as often as they could be caught for a long time. But Spain continued its

protests against English pirates by threatening – and later waging- war.

Queen Elizabeth I, who loved pirates (and the money they

brought home to England), knighted many of the original Buccaneers.

But when the true Golden Age of Piracy began, the rhetoric

changed yet again. Suddenly pirates were “the enemies of God and men” “the scourge

of all nations” “savages” and “unnatural.”

What changed?

The difference was that this time, the people in charge of

the raiding, weren’t rich, and for the first time, the entities being robbed

were neither nations nor individuals, but corporations. Individuals who are robbed don’t have a lot of

recourse, and nations have a certain tolerance for small robberies, since doing

something about it requires a lot of work.

Up until this point, raiding had been a rich man’s game. You

needed the boat, and weapons, and that ran into a ton of money. Even if you

weren’t rich yourself, you could become a pirate by convincing someone to give

you command of their boat. So, when the profits were shared out, the owner and

the captain got the largest share, and most of the cash stayed in the hands of

the “upper crust”.

But corporations – and entities like the English East India

Company (who later became powerful enough to maintain their own army and start

their own wars) the West Indian Company, the Dutch West India Company, etc were

insanely sensitive about being robbed, and they had the political clout to do something

about it. They started the rhetoric that still echoes in the image of pirates

being “evil” which lives on until this day. Highway robbers like Robin Hood

have been romantic figures for a long time. Pirates, not so much.

In addition to ticking off the merchant corporations, early 18th century pirates also won

the ire of insurance companies. Yes, almost all of the pirate’s victims had

insurance. So, a small-time merchant might be annoyed by being robbed, but it probably

wouldn’t ruin him. This may even have figured into the motives of certain

pirates. Even today, fleecing an insurance company doesn’t carry the social

disapproval of a “real crime”.

Pirates, usually working-class guys who had been repeatedly

screwed by “the system” stood up for themselves when they captured treasure. They

did not turn their prizes over to governments or financial backers. They kept

it for themselves, and often flaunted laws which said that only people of hereditary

wealth could wear certain clothing or eat certain foods.

When the powers that be saw “peasants” acting like they had

just as much right to nice clothing and good food as rich folks, they went

berserk. “God” had decided that certain people deserved to be rich, and He had

showed His choices by making those people rich himself. That uneducated men,

with no family connections or social standing should suddenly proclaim that they

had just as much money as the next guy overturned a world-view that had stood

for millennia.

Of course, pirates were not the only ones who were fighting

this fight. On land, people displaced by their landlords, workers whose wages had been reduced to below

poverty wages, mistreated apprentices, and others combined into riotous mobs

and fought for their rights.

The English government, influenced by the newly prosperous

middle class, and by corporations and merchant associations, tried to control

the lower classes by the use of harsher and harsher penalties, until well over

two hundred crimes were punishable by death. It did not have much effect.

Being a pirate, helping pirates, and doing business with

pirates was all illegal, but the penalties fell harshest on the deckhand level

pirates that the authorities happened to catch. The authorities simply could

not stand poor people who claimed to be just as good as the rich folks around

them.

Many rich people still can’t. Statements like “Those laws

don’t apply to us,” “Everyone can be rich if they just work hard enough,” and “Forty

seven percent of people just want handouts,” prove that there’s nothing a rich

person hates more than a poor person who wants to be equal.

Monday, July 13, 2015

A True, Modern Pirate Story

Pirates are known to inhabit just about anyplace there are boats.

But the sea-robbers are most common where law-and-order is scant, where islands

or uninhabited coastline provides convenient hiding places, and where

unidentified people can come and go without arousing suspicion.

The Caribbean of the 18th century was just such a

place, but many other parts of the earth also qualify. Today’s pirate story

takes place in the South China Sea, a place that has been famous for its

pirates almost from the dawn of recorded time.

We open in about 1974, when a woman named

France Guillain, of mixed French and Malaysian decent, took to sea in a 30-foot pirogue sailboat with her

five children. She would remain on the boat, off-and-on, for nearly 14 years,

experiencing life among sailors, natives and pirates. She wrote of her

experiences in a feminist book titled Les Femmes d’abord . The book is available only in French, but this tale has been

translated.

France was traveling from Hong Kong. She had held a course

between Taiwan and China, and was now among the small, wild inlets northwest of

the island of Luzon, largest island of the Philippines. This was an area that met all of the requirements

for pirates, but France was not feeling particularly afraid, in spite of the

fact that she had been warned.

“Do not,” she had been told, “go into any of the inlets. It

is far better to spend the night in your boat on the open sea. The whole area

is infested with the most dangerous of pirates, and they frequently spend their

evenings in these private inlets. Stay away!”

But, while not a reckless woman – for she could not have

been, and kept her family safe so far on her journey - on this particular evening,

France decided to ignore the warnings she had heard and pull into a sheltered

cove for the night. Below her keel were rough coral reefs, and the tides and

currents between them made ripping out the bottom of her fragile craft a real possibility.

She investigated such a cove during the late afternoon, and

was encouraged to find two other pirogue boats already pulled up on the shore. She heaved a

sigh of relief when she noticed children paying beside the craft. Women were in

the early stages of preparing food, and a grandmotherly type watched over a

sleeping infant. In all, there were nearly 30 people, whose interest was

centered around their campfire, and the two cooking pots hung over it.

The group appeared to simply be traveling natives. When

France beached her boat and approached the group, she was warmly greeted in English

by a man who introduced himself and his wife, Linda.

Linda and France spoke no common language, but they were held together by the bonds of womanhood and motherhood, and were almost immediately friendly. Together they watched France’s girls play with the native children, and worked together to finish preparing the meal.

As evening fell, France noticed that the circling headlands would hide the light of the group's fire from

pirates upon the open sea. She felt even more safe with her new friends.

After eating, the young men of the group pulled out ukuleles

, and sang while Linda danced. France recognized the tune, and felt that she

was back in her home in Tahiti. She sang a song of her own, and the young men

had no trouble picking up the tune. Then Linda showed her some dance steps, and

they danced together under the stars.

France took her dozing children back to their boat to sleep,

while Linda and her husband held some sort of serious discussion. Overhead, the stars were bright. France felt

secure in the safety of the surrounding cliffs and near the presence of the

large group of peaceful islanders. Surely no pirates would dare attack her

here.

Just as she was tucking in her sleepy girls, Linda’s husband

approached her with something important to say. “You must never come to these

coves again,” he said seriously. “It’s not safe.”

“Why?” France laughed in return. “Because of pirates?”

“Yes,” said the man. “They have no mercy. They kill

everyone, even the children. Linda is afraid something bad will happen to you.”

“Is she afraid of pirates?”

“WE are the pirates!” the man told her. Then he led here to one of his two boats, where France saw piles of electronics, nautical equipment – and machine guns.

“WE are the pirates!” the man told her. Then he led here to one of his two boats, where France saw piles of electronics, nautical equipment – and machine guns.

“Go now.” The man told her. “Don’t come back.”

Linda, her parents, and her children, were part of a tribe

of hereditary pirates, born and bred to the trade. Was France saved because the

pirates were already loaded with plunder? Because they didn’t want to foul the

white sand of their hiding place with her blood? Or because she knew the same

songs they did, and was not too shy to dance?

This story took place in 1974.

Monday, July 6, 2015

Were Pirates Gay?

One of the most persistent questions asked of this blog is always, "Were pirates gay?" I have an article about homosexuality among pirates here, stating that pirates were no more or less homosexual than any other sailors at the time, but that they did not criminalize the behavior.

But I don't think this answers the question. Pirates were referred to at the time, as "Gaye Fellowes". What's up with that? Why is the word so often used?

The fact is, pirates WERE gay. They were NOT homosexual.

The secret here is that words change in meaning, and the word "Gay" has changed a lot since it came into the English language.

When I write this - that words change in meaning - I can almost hear someone shouting, "No, they don't! Words mean things. They always mean the same things. Just look in a dictionary!" Yes, I know, the idea that language isn't always the same is disturbing to some people. But language NEEDS to change, to keep up with our changing world. And if you doubt me, get a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary, which gives the history of the meaning of each word it contains, and start reading up on how the meanings of some words has evolved.

Sometimes new words come into being. Words like "internet" "flashmob" "television" and even "airplane" were invented because new things were invented. Similarly, as people come to think differently about existing things, the words used to describe those things change.

Face it, there was a point in time where "bad" meant "good".

The word "gay" came to English from the French gai, some time about 1100. It meant "carefree, happy, having a good time". People spoke of being gay, having a gay time, and it had nothing to do with homosexuality.

However, England was a Protestant nation, and during the 1600's it began to adhere to what is called The Protestant Work Ethic. This philosophy says if you are not working, you're probably up to no good. The saying "Idle hands are the devil's workshop" pretty well sums it up. If you were working (planting wheat, weaving cloth, cooking) that was fine, but if you were not actively at work, you should still be doing something useful. like learning to play the piano or reading your Bible.

(This ideal reached its peak in the Industrial Age, when factory owners claimed that it was good for their employees to work 14-hour days, because otherwise they would be "idle".)

So, the word "gay" began to mean fooling around, sitting on your butt, or just generally being irresponsible. By about 1700, the word referred to someone who was spending too much time doing things that society didn't approve of, such as drinking, eating fine food, dancing, singing, or having sex. So the word was perfect for pirates. They loved to sing, dance, eat, drink and have sex, and society didn't approve of them at all.

Later, the word changed in meaning once again. During the 1800's it became a euphemism (word used because in place of another word that sounds too rude, crude or clinical) to talk about someone who was having too much sex, and with too many people.

You can still see echos of this in old black-and-white Hollywood movies. A woman will ask a man, "Don't you think I'm gay company?" and it probably means "Don't you think I'm good in bed?" During the same time period, "having a few laughs" could mean "having sex". People weren't comfortable talking about sex, and a person who was uptight could easily pretend that "gay" still meant "happy".

From there it was an easy step for homosexuals to use "gay" as a code word. Remember, up until 1962 it was illegal for two men to have sex in the United States, and people who were caught doing it could be sent to jail for years. And in England, just being gay (not even doing anything about it) brought a jail term and/or castration. So it was really, really important to have an innocent way to hint at what you were. Later, when homosexual men began to fight for the right to be themselves without penalty, they adopted the word "gay" officially, because "homosexual" sounded too much like a disease.

So: Pirates were gay, according to the use of the word during their time period, but were not homosexual. The word changed meanings.

Another sea-faring word that has changed meaning over the years is the word "Bully" Today it means a person who torments or picks on people who have difficulty fighting back. Bullies are accepted as being cowards.

In the Golden Age of Pirates however, the word had almost exactly the opposite meaning. Being "bully" meant being "like a bull". In other words, strong, self-assured, and brave. Sailors, who faced terrifying dangers at sea, and often went ashore in ports where they didn't speak the language and didn't know the customs, took pride in being "bully". They went into strange places and faced real danger and felt no fear. (Of if they did, they hid it extremely well.)

Sea Shanties like "Heave Away Me Bully Boys" and "Bully in the Alley" still remain as a testament to this time.

However, as Europe expanded her powers into the Third World, colonizing existing nations, these same visiting sailors (and soldiers) began to believe that they had the right to impose their own culture on conquered nations. If they didn't like the way native people were acting they might start a fight. If they believed that a woman was dressed like a prostitute, they might rape her. Since they were in a conquered nation, they felt they could "throw their weight around." In short, these men became "bullies" in the modern sense.

But I don't think this answers the question. Pirates were referred to at the time, as "Gaye Fellowes". What's up with that? Why is the word so often used?

The fact is, pirates WERE gay. They were NOT homosexual.

The secret here is that words change in meaning, and the word "Gay" has changed a lot since it came into the English language.

When I write this - that words change in meaning - I can almost hear someone shouting, "No, they don't! Words mean things. They always mean the same things. Just look in a dictionary!" Yes, I know, the idea that language isn't always the same is disturbing to some people. But language NEEDS to change, to keep up with our changing world. And if you doubt me, get a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary, which gives the history of the meaning of each word it contains, and start reading up on how the meanings of some words has evolved.

Sometimes new words come into being. Words like "internet" "flashmob" "television" and even "airplane" were invented because new things were invented. Similarly, as people come to think differently about existing things, the words used to describe those things change.

Face it, there was a point in time where "bad" meant "good".

The word "gay" came to English from the French gai, some time about 1100. It meant "carefree, happy, having a good time". People spoke of being gay, having a gay time, and it had nothing to do with homosexuality.

However, England was a Protestant nation, and during the 1600's it began to adhere to what is called The Protestant Work Ethic. This philosophy says if you are not working, you're probably up to no good. The saying "Idle hands are the devil's workshop" pretty well sums it up. If you were working (planting wheat, weaving cloth, cooking) that was fine, but if you were not actively at work, you should still be doing something useful. like learning to play the piano or reading your Bible.

(This ideal reached its peak in the Industrial Age, when factory owners claimed that it was good for their employees to work 14-hour days, because otherwise they would be "idle".)

So, the word "gay" began to mean fooling around, sitting on your butt, or just generally being irresponsible. By about 1700, the word referred to someone who was spending too much time doing things that society didn't approve of, such as drinking, eating fine food, dancing, singing, or having sex. So the word was perfect for pirates. They loved to sing, dance, eat, drink and have sex, and society didn't approve of them at all.

Later, the word changed in meaning once again. During the 1800's it became a euphemism (word used because in place of another word that sounds too rude, crude or clinical) to talk about someone who was having too much sex, and with too many people.

You can still see echos of this in old black-and-white Hollywood movies. A woman will ask a man, "Don't you think I'm gay company?" and it probably means "Don't you think I'm good in bed?" During the same time period, "having a few laughs" could mean "having sex". People weren't comfortable talking about sex, and a person who was uptight could easily pretend that "gay" still meant "happy".

From there it was an easy step for homosexuals to use "gay" as a code word. Remember, up until 1962 it was illegal for two men to have sex in the United States, and people who were caught doing it could be sent to jail for years. And in England, just being gay (not even doing anything about it) brought a jail term and/or castration. So it was really, really important to have an innocent way to hint at what you were. Later, when homosexual men began to fight for the right to be themselves without penalty, they adopted the word "gay" officially, because "homosexual" sounded too much like a disease.

So: Pirates were gay, according to the use of the word during their time period, but were not homosexual. The word changed meanings.

Another sea-faring word that has changed meaning over the years is the word "Bully" Today it means a person who torments or picks on people who have difficulty fighting back. Bullies are accepted as being cowards.

In the Golden Age of Pirates however, the word had almost exactly the opposite meaning. Being "bully" meant being "like a bull". In other words, strong, self-assured, and brave. Sailors, who faced terrifying dangers at sea, and often went ashore in ports where they didn't speak the language and didn't know the customs, took pride in being "bully". They went into strange places and faced real danger and felt no fear. (Of if they did, they hid it extremely well.)

Sea Shanties like "Heave Away Me Bully Boys" and "Bully in the Alley" still remain as a testament to this time.

However, as Europe expanded her powers into the Third World, colonizing existing nations, these same visiting sailors (and soldiers) began to believe that they had the right to impose their own culture on conquered nations. If they didn't like the way native people were acting they might start a fight. If they believed that a woman was dressed like a prostitute, they might rape her. Since they were in a conquered nation, they felt they could "throw their weight around." In short, these men became "bullies" in the modern sense.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)